Lessons From Iraq: The Hottest, Deadliest Month of My Life

Surviving ‘Fire Month’ in Iraq August 2003.

Last week I dropped off my daughter Maggie at Clemson—some of you may have read my substack piece on that. I did all the dad things: carried boxes, helped her set up, took her out to eat, bought merch from the college bookstore, and not embarrass her with too many hugs.

But as we toured the football stadium, dubbed “Death Valley”, my mind slipped somewhere else.

Suddenly, I wasn’t in South Carolina anymore.

It unlocked a cascade of memories. Unbeknownst to her and her brother, their easy conversations went on without me as my mind drifted back 22 years. First, it made me think of the real Death Valley, in California’s Mojave Desert, the hottest place on earth, where summer temperatures regularly peak over 100 degrees. And that association brought me back to the hottest place I ever endured: Living through the 135-degree inferno of Baghdad, Iraq, while wearing combat gear, and a month of my life that still feels scorched into memory:

August 2003.

We all called it ‘Fire Month,’ because that was the only way to explain what it felt like to live through it.

Just two months before my deployment, I had been teaching constitutional law at West Point at Thayer Hall, grading finals and wishing my cadets well as they went off into the world. Within weeks, I was in Baghdad with the 82nd Airborne Division, a 29-year-old captain leading a Brigade Operational Law Team (BOLT), suddenly responsible for building a justice system for 1.5 million Iraqis while surviving the most violent month of our deployment.

It was scary. But I knew my duty.

I had two jobs.

First, I was the only lawyer for 3,500 paratroopers prosecuting high-level terrorists, running Article 15s, and trying to build a justice system in a city torn apart.

Secondly, I was leading convoys, dodging Improvised Explosive Devices (IEDs), and getting mortared almost nightly at our forward operating base in south central Baghdad.

The conditions were brutal. We didn’t really have plumbing. We eventually had Porta-johns (better than the burn pits). They were basically plastic ovens that stank to high heaven. You’d walk in to do your business a little sweaty but leave completely drenched, and if it was a #2, you had to navigate through the flies that would climb from below onto your ass cheeks.

Showers? Maybe weekly. We washed and shaved mostly with water bottles and the rear-view mirrors of our Humvee.

They said our mission was to “win hearts and minds.” But it was often just survival.

Did I question why we were there? Absolutely - before, during, and after the deployment. My soldiers did too. But I never ever voiced it. I made sure we were focused on the brutal task at hand. Their morale mattered more than my doubts.

Most of us were in our 20s and 30s, carrying the weight of history on our shoulders. Some carried it home. Some never did.

Our 82nd Airborne Division's second brigade combat team in Iraq, 3,500 strong, lost 19 paratroopers. I personally knew several of them. Some I knew like a brother.

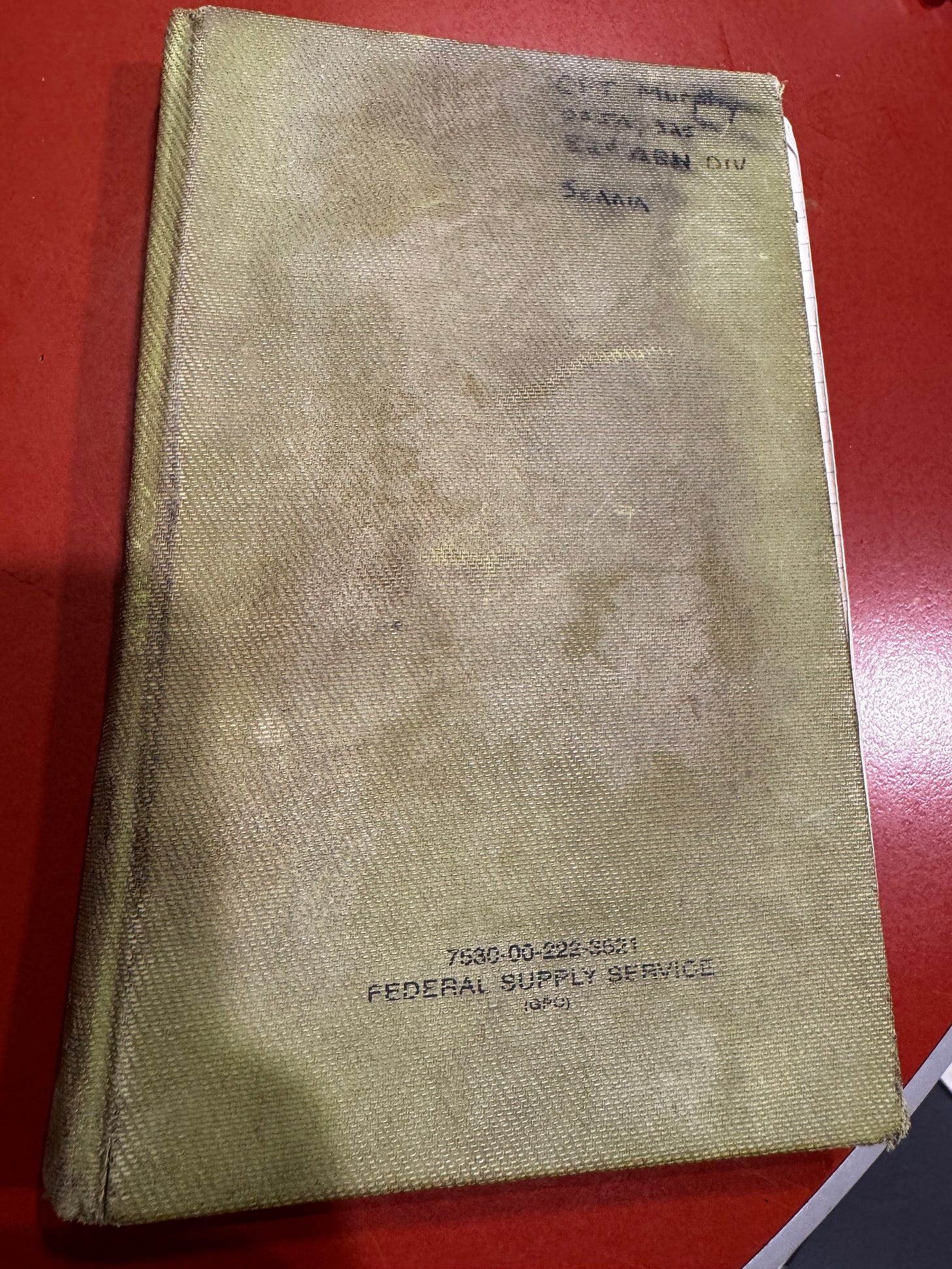

I’ve kept journals for most of my adult life. When I came home from Clemson, I opened up my Army-issued green book for the first time in over a decade.

What follows is a glimpse at what that hellish month was like. Words hardly capture it.

Aug 1: Six IEDs exploded in one day. A five-year-old was kidnapped. His parents received a ransom note—and later, his fingers in the mail. PVT Deutch killed by an IED and PFC Lambert killed when he was shot in the head by a stray bullet from celebratory fire 24 hours earlier.

Aug 7: A car bomb at the Jordanian Embassy. Three hundred pounds of explosives. At least eight killed.

Aug 8: PFC Longstreth, on guard duty, died by suicide.

Aug 11: Ten soldiers wounded by IEDs in a single day.

Aug 12: We took another two mortar rounds last night, while another one hit our 1BN FOB.

Aug 13: A group of about 20 of us were briefed by General Marty Dempsey. He gave us three orders: 1. Finish the fight. 2. Make a positive difference in the lives of the Iraqi people. 3. Take care of your troops.

Aug 15: The Feast of the Assumption. A holy day for Catholics. For me, a day I had to deliver a “solatia” or “consolation payment” of $1,500 to an Iraqi family whose son was mistakenly killed by U.S. fire. Seven direct fire engagements, 5 IEDs in our sector.

Aug 19: UN Embassy up the road in Baghdad bombed. UN Ambassador killed. At least 14 killed.

Aug 27: Our 24-year-old interpreter, Alyaa, fell out of our lead Humvee, as we raced around the traffic circle on the north side of the July 14th bridge. She was scratched up pretty bad, but continued the mission.

Aug 29: Convoy hit by IED, 1 WIA, 4 Iraqis wounded, 1 Iraqi killed. Shrapnel stuck in window, just missing by five inches from decapitating one of our guy’s head, small picture of Jesus Christ right there in the corner of the Humvee’s window, surrounding the web of broken glass. That same day, a car bomb killed 75 and wounded 300 in Najaf, 100 miles south of Baghdad.

Aug 30: I attended 1 o’clock Mass. A priest from Baghdad just happened to show up—our first since deployment, since we didn’t have a Catholic chaplain. In his sermon, he thanked us for being “the hand of mercy.” He reminded us how, when troops arrived months earlier, Christians told them to help the Muslims first. In 1991, Christians were forced from their homes up north, leaving everything behind, but they built churches before homes. His optimism and gratitude touched me deeply.

Aug 31: SPC Juan ‘RV’ Arevalo wins Paratooper of the Quarter. He’s excited about the CSM coin & the free dress blues he’ll get when he gets home.

So yeah—that month in Iraq was a lot. But there were also life-affirming moments that reminded me why I was there.

Late one night that August, I was chatting with Sergeant Sean Scarborough, our Noncommissioned Officer in Charge, who made it home from deployment but is no longer with us. He told me, “Sir, you’re different. You actually care. You and RV have love for the Iraqi people. You really are different from most trial counsel. You have compassion.” And I was like, “I hope you don't think my compassion stops me from crushing someone in an instant.”

“No, Sir, that’s what’s so cool about it.”

***

Lessons Learned

Embrace the Suck. The heat hit 135 degrees. Discipline is more important than motivation. Lead with love and find a way to laugh.

Cherish Your Loved Ones. You might not see them tomorrow. You never know when you’re time is up. Make it count every day.

Enjoy the Simple Things. The way a bottle of cold water could taste like heaven. The way a laugh could keep you sane. Hot showers. Toilets without flies. Hot meals. Friends that won’t be taken from you suddenly on a normal basis.

These are the things I was thinking about while bringing my daughter to college and reflecting on now. I’m also thinking about how proud I am that she’s entering her own journey as part of the warrior class. The road for her or any of our young Americans willing to sacrifice it all will never be easy. But thank God we have people like them who love our nation with a servant’s heart.

In three weeks, this upcoming 9/11 (24 years later!) I’ll be standing tall at the George W. Bush Presidential Library in Dallas alongside veteran leaders across this nation, including my friend “RV”—the paratrooper of the quarter I once encouraged to apply to West Point late one night in Baghdad. He went on marry a classmate and become a Texas State Trooper, a lawyer and father.

— Patrick

The Honorable Patrick J. Murphy is a Wharton lecturer, Vetrepreneur, and the 32nd Army Under Secretary after earning the Bronze Star for service in Baghdad, Iraq as an All-American with the 82nd Airborne Division—@PatrickMurphyPA on Instagram and Twitter.

Thank you for reminding us what a real patriot is like.

Love this part:

“Late one night that August, I was chatting with Sergeant Sean Scarborough, our Noncommissioned Officer in Charge, who made it home from deployment but is no longer with us. He told me, “Sir, you’re different. You actually care. You and RV have love for the Iraqi people. You really are different from most trial counsel. You have compassion.” And I was like, “I hope you don't think my compassion stops me from crushing someone in an instant.”

“No, Sir, that’s what’s so cool about it.”

Anyone who knows you knows this is true, lolll